余積

双対としてよく知られているものに、積の双対である余積 (coproduct、「直和」とも) がある。双対を表すのに英語では頭に “co-” を、日本語だと「余」を付ける。

以下に積の定義を再掲する:

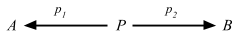

定義 2.15. 任意の圏 C において、対象 A と B の積の図式は対象 P と射 p1 と p2 から構成され

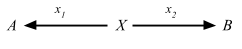

以下の UMP を満たす:この形となる任意の図式があるとき

次の図式

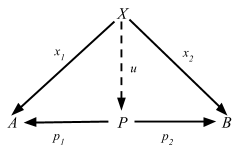

が可換となる (つまり、x1 = p1 u かつ x2 = p2 u が成立する) 一意の射 u: X => P が存在する。

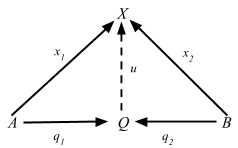

矢印をひっくり返すと余積図式が得られる:

余積は同型を除いて一意なので、余積は A + B、u: A + B => X の射は [f, g] と表記することができる。

「余射影」の i1: A => A + B と i2: B => A + B は、単射 (“injective”) ではなくても「単射」 (“injection”) という。

「埋め込み」(embedding) ともいうみたいだ。積が scala.Product などでエンコードされる直積型に関係したように、余積は直和型 (sum type, union type) と関連する:

data TrafficLight = Red | Yellow | Green

Unboxed union types

case class や sealed trait を使って直和型をエンコードすると、例えば Int と String の union を作ろうとしたときにうまくいかない。これに関して面白いのが Miles Sabin (@milessabin) さんの Unboxed union types in Scala via the Curry-Howard isomorphismだ。

誰もがド・モルガンの法則は見たことがあると思う:

!(A || B) <=> (!A && !B)

Scala には A with B 経由で論理積があるため、Miles は否定さえエンコードできれば論理和を得られることを発見した。これは Scalaz では scalaz.UnionTypes として移植された:

trait UnionTypes {

type ![A] = A => Nothing

type !![A] = ![![A]]

trait Disj { self =>

type D

type t[S] = Disj {

type D = self.D with ![S]

}

}

type t[T] = {

type t[S] = (Disj { type D = ![T] })#t[S]

}

type or[T <: Disj] = ![T#D]

type Contains[S, T <: Disj] = !![S] <:< or[T]

type ∈[S, T <: Disj] = Contains[S, T]

sealed trait Union[T] {

val value: Any

}

}

object UnionTypes extends UnionTypes

Miles の size の例を実装してみる:

scala> import UnionTypes._

import UnionTypes._

scala> type StringOrInt = t[String]#t[Int]

defined type alias StringOrInt

scala> implicitly[Int ∈ StringOrInt]

res0: scalaz.UnionTypes.∈[Int,StringOrInt] = <function1>

scala> implicitly[Byte ∈ StringOrInt]

<console>:18: error: Cannot prove that Byte <:< StringOrInt.

implicitly[Byte ∈ StringOrInt]

^

scala> def size[A](a: A)(implicit ev: A ∈ StringOrInt): Int = a match {

case i: Int => i

case s: String => s.length

}

size: [A](a: A)(implicit ev: scalaz.UnionTypes.∈[A,StringOrInt])Int

scala> size(23)

res2: Int = 23

scala> size("foo")

res3: Int = 3

\/

Scalaz にある \/ も、直和型の一種だと考えることができる。シンボルを使った名前である \/ も、∨ が論理和 (logical disjunction) を表すことを考えると納得がいく。これは7日目 でカバーした。 size の例を書き換えるとこうなる:

scala> def size(a: String \/ Int): Int = a match {

case \/-(i) => i

case -\/(s) => s.length

}

size: (a: scalaz.\/[String,Int])Int

scala> size(23.right[String])

res15: Int = 23

scala> size("foo".left[Int])

res16: Int = 3

Coproduct と Inject

Scalaz には実は Coproduct もあって、これは型コンストラクタのための Either のようなものだ:

final case class Coproduct[F[_], G[_], A](run: F[A] \/ G[A]) {

...

}

object Coproduct extends CoproductInstances with CoproductFunctions

trait CoproductFunctions {

def leftc[F[_], G[_], A](x: F[A]): Coproduct[F, G, A] =

Coproduct(-\/(x))

def rightc[F[_], G[_], A](x: G[A]): Coproduct[F, G, A] =

Coproduct(\/-(x))

...

}

Data types à la carte で、Wouter Swierstra (@wouterswierstra) さんがこれを使っていわゆる Expression Problem と呼ばれているものを解決できると解説している:

目標は、既にあるコードを再コンパイルしたり型安全性を失うこと無く、ケースごとにデータ型を定義して、データ型に新たなケースを追加したり、データ型を受け取る新たな関数を定義できるようにすることだ。

この論文で述べられている automatic injection は、@ethul によって #502 で Scalaz にコントリビュートされた。具体例は typeclass-inject の README を参照してほしい。

それぞれの式は Free[F, Int] を構築していて、F は 3つの代数系の余積となっている。