- Coproduct

Coproduct

One of the well known duals is coproduct, which is the dual of product. Prefixing with “co-” is the convention to name duals.

Here’s the definition of products again:

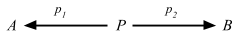

Definition 2.15. In any category C, a product diagram for the objects A and B consists of an object P and arrows p1 and p2

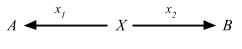

satisfying the following UMP:Given any diagram of the form

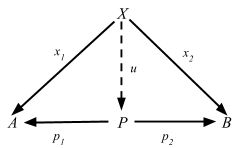

there exists a unique u: X => P, making the diagram

commute, that is, such that x1 = p1 u and x2 = p2 u.

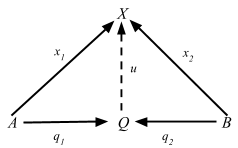

Flip the arrows around, and we get a coproduct diagram:

Since coproducts are unique up to isomorphism, we can denote the coproduct as A + B, and [f, g] for the arrow u: A + B => X.

The “coprojections” i1: A => A + B and i2: B => A + B are usually called injections, even though they need not be “injective” in any sense.

Similar to the way products related to product type encoded as scala.Product, coproducts relate to the notion of sum type, or disjoint union type.

Algebraic datatype

First way to encode A + B might be using sealed trait and case classes.

sealed trait XList[A]

object XList {

case class XNil[A]() extends XList[A]

case class XCons[A](head: A, rest: XList[A]) extends XList[A]

}

XList.XCons(1, XList.XNil[Int])

// res0: XList.XCons[Int] = XCons(head = 1, rest = XNil())

Either datatype as coproduct

If we squint Either can be considered a union type. We can define a type alias called |: for Either as follows:

type |:[+A1, +A2] = Either[A1, A2]

Because Scala allows infix syntax for type constructors, we can write Either[String, Int] as String |: Int.

val x: String |: Int = Right(1)

// x: String |: Int = Right(value = 1)

Thus far I’ve only used normal Scala features only. Cats provides a typeclass called cats.Inject that represents injections i1: A => A + B and i2: B => A + B. You can use it to build up a coproduct without worrying about Left or Right.

import cats._, cats.data._, cats.syntax.all._

val a = Inject[String, String |: Int].inj("a")

// a: String |: Int = Left(value = "a")

val one = Inject[Int, String |: Int].inj(1)

// one: String |: Int = Right(value = 1)

To retrieve the value back you can call prj:

Inject[String, String |: Int].prj(a)

// res1: Option[String] = Some(value = "a")

Inject[String, String |: Int].prj(one)

// res2: Option[String] = None

We can also make it look nice by using apply and unapply:

lazy val StringInj = Inject[String, String |: Int]

lazy val IntInj = Inject[Int, String |: Int]

val b = StringInj("b")

// b: String |: Int = Left(value = "b")

val two = IntInj(2)

// two: String |: Int = Right(value = 2)

two match {

case StringInj(x) => x

case IntInj(x) => x.show + "!"

}

// res3: String = "2!"

The reason I put colon in |: is to make it right-associative. This matters when you expand to three types:

val three = Inject[Int, String |: Int |: Boolean].inj(3)

// three: String |: Int |: Boolean = Right(value = Left(value = 3))

The return type is String |: (Int |: Boolean).

Curry-Howard encoding

An interesting read on this topic is Miles Sabin (@milessabin)’s Unboxed union types in Scala via the Curry-Howard isomorphism.

Shapeless.Coproduct

See also Coproducts and discriminated unions in Shapeless.

EitherK datatype

There’s a datatype in Cats called EitherK[F[_], G[_], A], which is an either on type constructor.

In Data types à la carte Wouter Swierstra (@wouterswierstra) describes how this could be used to solve the so-called Expression Problem.

That’s it for today.