fast Scala 3 parsing with tree-sitter

Sometime in 2021 I had the pleasure to be on Chris Kipp’s Tooling Talks podcast. One of the questions I prepared is what is tooling. I consider myself a programmer, but I do recognize tooling people in different companies, so there must be something to it. One analogy that I used was that when building a house or an musical instrument, most people are cutting wood etc that would go into the house or the instrument, but there are a few people on the side rigging up something that would make the cut more efficient, by cutting 10 things at the same time, or cutting it easier for the angle specific to the house. They are tooling people.

Maybe because I hang out with other tooling people, for a few years I’ve been hearing about Tree-sitter, or some Tree-sitter grammar this and that, but didn’t get into it until last week.

what is Tree-sitter?

Tree-sitter is a parser generator tool and an incremental parsing library, originally announced in 2017 by Max Brunsfeld after 4 years of working on it as a side project, and later as a Github engineer. His Strange Loop talk is a great intro to Tree-sitter. In the talk he said that Tree-sitter was used for parsing in Atom and some experimental features in github.com.

To get started, install the Tree-sitter command line tool called tree-sitter, which interprets your grammar.js to generate a parser code in C. The workflow is reminisent of yacc/bison parser generation that I learned in college.

Compared to performing regex at runtime, which is what more common parsing libraries would do, one advantage of these generator is that they’ve broken them down into a finite state machine, and parses at fast speed.

A few interesting features of Tree-sitter are that its capable of incremental parsing, and also its capable of parsing code that contains errors. These two aspects make Tree-sitter particularly useful for language features in editors, like syntax highlight and code folding.

Analogous to the Language Server Protocol (LSP), Tree-sitter on its own is unaware of specific programming languages, but once the C code is generated for the language you’re interested in, it could be invoked programmatically to annotate the source code with the syntax. One way of thinking about this that tree-sitter CLI is capable of turning any source code into LISP. Once the code is in the common format, other people can write common tooling to manipulate it, like highlighting (and more features).

Neovim, Tree-sitter, and Scala

Vim has a built-in syntax highlight feature, mostly based on keyword searches, and while it’s searvicable, compared to editors like Sublime Text and VS Code, the highlighting seems less accurate. There’s an experimental Tree-sitter support in Neovim, which in theory can improve the accuracy. You can follow nvim-treesitter to enable hightlighting using Tree-sitter in current Neovim.

When I tried this out last Tuesday, the highlighting for Scala 3’s new optional brace syntax was pretty bad. As mentioned, Tree-sitter on its own is unaware of specific programming languages, but there is a separate repo called tree-sitter/tree-sitter-scala that’s maintaining the Tree-sitter grammar for Scala, and that seems to not support the new syntax introduced by Scala 3 yet.

Once Tree-sitter can process Scala 3 code, it provides much richer annotation (also known as scopes) of the language, that we can create better syntax highlighting, and other features beyond highlighting using the parsed syntax tree. While this might be a pinacle of the law of triviality – color of paint to put on the bikeshed – as a Scala 3 enthusiast on a winter vacation, I felt like this yacc was calling for me.

conversion from EBNF

Scala 3’s syntax is available on Scala 3 Reference: Scala 3 Syntax Summary page as EBNF (extended Backus–Naur form). Ethan Atkins has an abandoned tree-sitter-ebnf-generator repo that potentially can convert between the two. I played with it a bit, but I don’t think I had the full context of tree-sitter at the time to make it work.

In general, though, while working a transription of a parser it’s useful and important to reference the EBNF of the syntax construct.

Earlier Scala syntax specification listed case blocks after

catch. In 2015 Som Snytt (@som_snytt@fosstodon.org) sent a proposal to generalize this in ‘Can catch any expression’ (scala/scala#4400). After years of review rounds, it was merged in 2021 as Scala 2.13.6.hacking on tree-sitter-scala

Working on tree-sitter-scala is straightforward once you get the hang of it.

npm install

Then make changes to test files in ./corpus. Then:

npm run build

npm test

The tree-sitter CLI itself is written in Rust. In the above, npm run build invokes the CLI, and the code generation is slow for tree-sitter-scala. On my old laptop, the process takes 5 minutes, but depending on the changes I make to the grammar it jumps to 10 ~ 40 minutes or just doesn’t seem to end. This means that even when I work on this all day, I can make 10 changes in an hour at best.

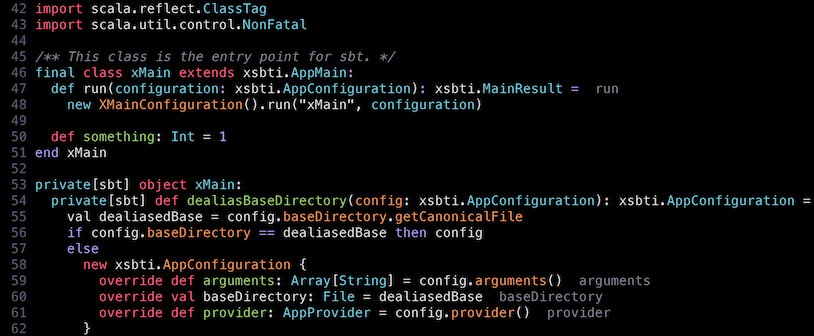

To get some idea about the status quo, here’s a snippet of Scala 3 syntax code, highlighted using Sonokai theme. Since the theme is Tree-sitter compatible, we can see different elements it tried to color:

Note that def run is not highlighted since it doesn’t recognize the optional braces syntax.

optional braces, part 1

Last Tuesday, I sent the first PR ‘Optional braces, part 1’ (#61), and here’s the main change:

- template_body: $ => seq(

- '{',

- // TODO: self type

- optional($._block),

- '}'

+ /*

+ * TemplateBody ::= :<<< [SelfType] TemplateStat {semi TemplateStat} >>>

+ */

+ template_body: $ => choice(

+ prec.left(PREC.end_decl, seq(

+ ':',

+ // TODO: self type

+ // TODO: indentation. currently second `val` declaration in the block will

+ // be treated as a top-level declaration instead of belonging to the template.

+ $._block,

+ optional($._end_signifier),

+ )),

+ seq(

+ '{',

+ // TODO: self type

+ optional($._block),

+ '}',

+ ),

),

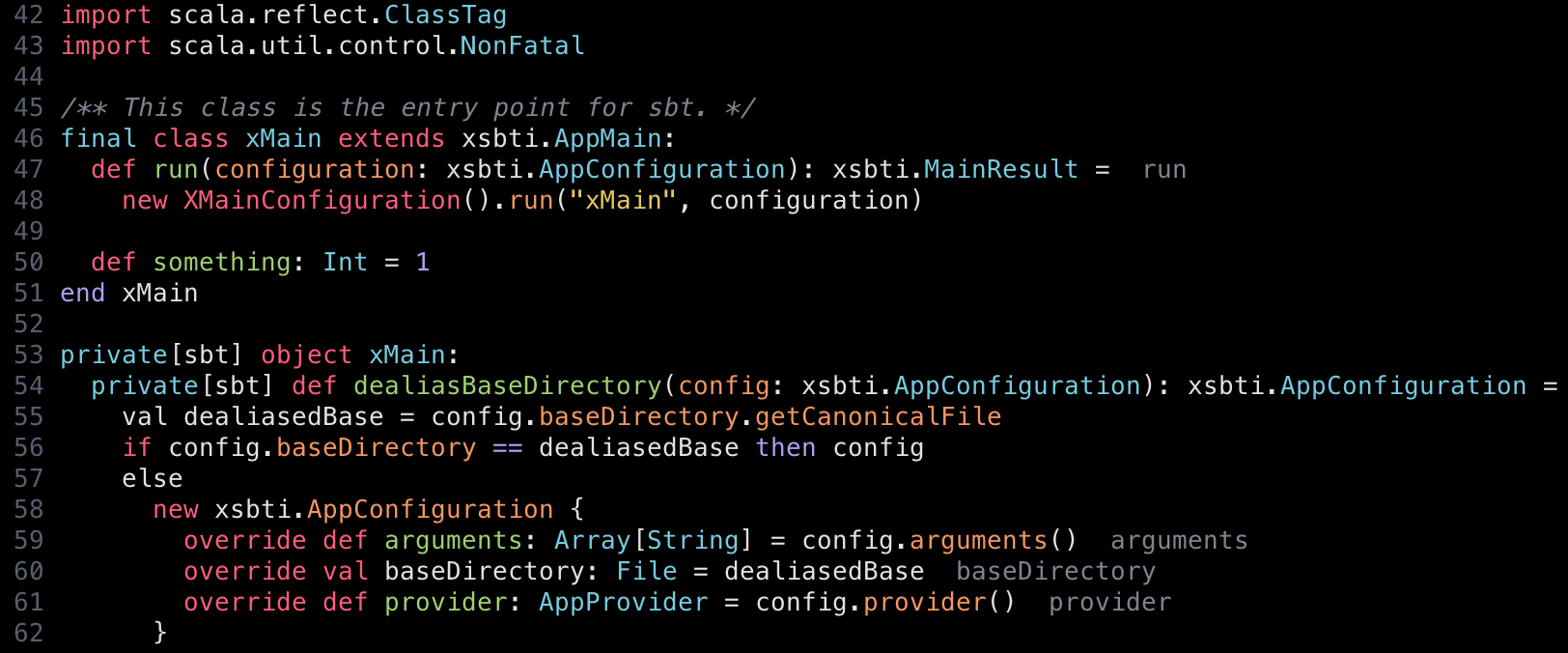

template_body is the body part of class and object definitions, and this change allows : instead of { ... }. It’s a small change and it won’t parse many things correctly, but we now see that def run is recognized as a method:

optional braces, part 2

In the above, note that val dealiasedBase is not correctly hightlighted.

This is because in Scala 2, val definition would’ve required to be inside a { ... } block.

We can certainly make another superficial fix by removing the requirement for { ... }, but generally in Scala 3’s optional braces syntax, we need to keep track of the indentation level to know which statement belongs to which construct.

class A:

def foo(): Unit =

val x = 1

val y = 2

In the above, val y belongs to def foo.

class A:

def foo(): Unit =

val x = 1

val y = 2

In the above, val y belongs to class A, not def foo.

class A:

def foo(): Unit =

val x = 1

val y = 2

In the above, val y becomes a top-level statement. Since there is a growing interest in this area, it’s not surprising that Anton Sviridov looked at it 2 weeks ago, and told me about his wip branch.

In the Tree-sitter grammar, the terminal tokens are described either with a plain string like

'def' or by using a regular expression, however there are situations where it’s impossible/inconvenient to describe with a regex. There’s a feature called external scanner, where you can provide programmatic scanner implementation in C. For example, tree-sitter-scala already uses external scanners to scan string literals, which makes sense since the handling of newline would be different inside """...""".What Anton had started in his work-in-progress branch was an implementation of an external scanner for indent/outdent that tracks the indentation level in a stack written in C. I can’t remember the last time I’ve written honest C since using Bison in college compilers course, so this Tree-sitter has a retro future vibe for me.

Using $._indent and $._outdent I’ve modified template_body and added a new _indentable_expression token, which we can use in places like if expression:

template_body: $ => choice(

prec.left(PREC.end_decl, seq(

':',

// TODO: self type

- // TODO: indentation. currently second `val` declaration in the block will

- // be treated as a top-level declaration instead of belonging to the template.

+ $._indent,

$._block,

+ $._outdent,

optional($._end_signifier),

)),

....

+ _indentable_expression: $ => choice(

+ $.indented_block,

+ $.expression,

+ ),

block: $ => seq(

'{',

optional($._block),

'}'

),

+ indented_block: $ => seq(

+ $._indent,

+ $._block,

+ $._outdent,

+ ),

To test the grammar, tree-sitter CLI supports test command that takes text files containing both a code snippet and expected S-expression:

=======================================

Function definitions (Scala 3 syntax)

=======================================

class A:

def foo(c: C): Int =

val x = 1

val y = 2

x + y

---

(compilation_unit

(class_definition

(identifier)

(template_body

(function_definition

(identifier)

(parameters

(parameter (identifier) (type_identifier)))

(type_identifier)

(indented_block

(val_definition (identifier) (integer_literal))

(val_definition (identifier) (integer_literal))

(infix_expression (identifier) (operator_identifier) (identifier)))))))

In the above, we can see that there are two val_declaration nodes, both belonging to indented_block. This is why I was saying that tree-sitter converts all source code into LISP. Without the indent/dedent tracking, we wouldn’t know for sure that val y belongs to def foo.

optional braces, part 2.a

One thing I noticed soon is that something like the following code failed to parse:

class A:

def foo(): Unit =

val x = 1

class B

Using tree-sitter CLI’s parse command we get:

$ tree-sitter parse examples/A.scala

(compilation_unit [0, 0] - [5, 0]

(class_definition [0, 0] - [5, 0]

name: (identifier [0, 6] - [0, 7])

body: (template_body [0, 7] - [5, 0]

(function_definition [1, 2] - [4, 0]

name: (identifier [1, 6] - [1, 9])

parameters: (parameters [1, 9] - [1, 11])

return_type: (type_identifier [1, 13] - [1, 17])

body: (indented_block [2, 4] - [4, 0]

(val_definition [2, 4] - [2, 13]

pattern: (identifier [2, 8] - [2, 9])

value: (integer_literal [2, 12] - [2, 13]))))

(ERROR [4, 0] - [4, 7]

(identifier [4, 0] - [4, 5])

(identifier [4, 6] - [4, 7])))))

examples/A.scala 0 ms (ERROR [4, 0] - [4, 7])

Note that even though it failed to parse part of the code (due to parser’s limitation), it managed to report majority of the tree, which it did parse instead of failing completely.

An earlier example that I showed actually also fails to parse:

class A:

def foo(): Unit =

val x = 1

val y = 2

To explain what’s happening let’s annotate INDENT and OUTDENT tokens into the code:

class A:

INDENT

def foo(): Unit =

INDENT

val x = 1

OUTDENT

val y = 2

The parser is expecting two OUTDENTs but instead it encounters class or val, and it errors.

This is basically a bug in indent/outdent tracking:

bool tree_sitter_scala_external_scanner_scan(void *payload, TSLexer *lexer,

const bool *valid_symbols) {

// read all the whitespaces and newlines

if (valid_symbols[OUTDENT] && newline_count > 0 && prev != -1 &&

indentation_size < prev) {

popStack(stack);

lexer->result_symbol = OUTDENT;

return true;

}

....

The scanner is called for each token, and it only return OUTDENT when the indentation_size decreases after a new line. This one its own is fine, but after the first OUTDENT, it will no longer hit the condition. My fix for this was to persist the indent level, and before processing further letters recheck in the beginning of the function if we can OUTDENT again:

bool tree_sitter_scala_external_scanner_scan(void *payload, TSLexer *lexer,

const bool *valid_symbols) {

ScannerStack *stack = (ScannerStack *)payload;

int prev = peekStack(stack);

// Before advancing the lexer, check if we can double outdent

if (valid_symbols[OUTDENT] &&

(lexer->lookahead == 0 || (

stack->last_indentation_size != -1 &&

prev != -1 &&

stack->last_indentation_size < prev))) {

popStack(stack);

lexer->result_symbol = OUTDENT;

return true;

}

stack->last_indentation_size = -1;

....

We can rebuild the Scala parser, and try again:

$ time npm run build && say ok

> tree-sitter-scala@0.19.0 build

> tree-sitter generate && node-gyp build

gyp info it worked if it ends with ok

gyp info using node-gyp@9.0.0

gyp info using node@18.4.0 | darwin | x64

gyp info spawn make

gyp info spawn args [ 'BUILDTYPE=Release', '-C', 'build' ]

CC(target) Release/obj.target/tree_sitter_scala_binding/src/parser.o

CXX(target) Release/obj.target/tree_sitter_scala_binding/bindings/node/binding.o

CC(target) Release/obj.target/tree_sitter_scala_binding/src/scanner.o

SOLINK_MODULE(target) Release/tree_sitter_scala_binding.node

gyp info ok

npm run build 129.23s user 260.38s system 55% cpu 11:41.38 total

$ tree-sitter parse examples/A.scala

(compilation_unit [0, 0] - [5, 0]

(class_definition [0, 0] - [4, 0]

name: (identifier [0, 6] - [0, 7])

body: (template_body [0, 7] - [4, 0]

(function_definition [1, 2] - [4, 0]

name: (identifier [1, 6] - [1, 9])

parameters: (parameters [1, 9] - [1, 11])

return_type: (type_identifier [1, 13] - [1, 17])

body: (indented_block [2, 4] - [4, 0]

(val_definition [2, 4] - [2, 13]

pattern: (identifier [2, 8] - [2, 9])

value: (integer_literal [2, 12] - [2, 13]))))))

(val_definition [4, 0] - [4, 9]

pattern: (identifier [4, 4] - [4, 5])

value: (integer_literal [4, 8] - [4, 9])))

This shows that val y is now parsed correctly as a child node of compilation_unit.

optional braces, part 2.b

Interestingly the following example also fails to parse for a different reason:

class A:

def foo: Int =

1

val y = 2

Looking at the error, it looks like val y = 2 fails to be part of class A.

This is likely outdent consumes the newline character, but the dection of automatic semicolon is required between the methods and fields within a template:

_block: $ => prec.left(seq(

sep1($._semicolon, choice(

$.expression,

$._definition,

$._end_marker,

)),

optional($._semicolon),

)),

_semicolon: $ => choice(

';',

$._automatic_semicolon

),

Similar to making the scanner persist the last indentation size, we need to persist the last newline count so the autosemicolon detection regains the newline count.

bool tree_sitter_scala_external_scanner_scan(void *payload, TSLexer *lexer,

const bool *valid_symbols) {

// read all the whitespaces and newlines

if (valid_symbols[OUTDENT] &&

(lexer->lookahead == 0 || (

newline_count > 0 &&

prev != -1 &&

indentation_size < prev))) {

popStack(stack);

LOG(" pop\n");

LOG(" OUTDENT\n");

lexer->result_symbol = OUTDENT;

stack->last_indentation_size = indentation_size;

stack->last_newline_count = newline_count;

stack->last_column = lexer->get_column(lexer);

return true;

}

// Recover newline_count from the outdent reset

if (stack->last_newline_count > 0 &&

lexer->get_column(lexer) == stack->last_column) {

newline_count += stack->last_newline_count;

}

....

Let’s try again:

$ time npm test

# test passed

$ tree-sitter parse examples/A.scala

(compilation_unit [0, 0] - [5, 0]

(class_definition [0, 0] - [5, 0]

name: (identifier [0, 6] - [0, 7])

body: (template_body [0, 7] - [5, 0]

(function_definition [1, 2] - [4, 2]

name: (identifier [1, 6] - [1, 9])

return_type: (type_identifier [1, 11] - [1, 14])

body: (indented_block [2, 4] - [4, 2]

(integer_literal [2, 4] - [2, 5])))

(val_definition [4, 2] - [4, 11]

pattern: (identifier [4, 6] - [4, 7])

value: (integer_literal [4, 10] - [4, 11])))))

This shows that val y is parsed correctly as part of the class.

optional braces, part 2.c

Once the basic indent/outdent started working, I added support for control structures,

like if, try, match, while, and for expression.

Since I am still getting up to speed on writing Tree-sitter grammar, and because each iteration takes a long time, it’s been a series of trial and errors. Here are some miscellaneous things that I ran into.

Tree-sitter vs context free grammer

I am not sure whether this is a specific characteristic of tree-sitter-scala implementation or if it’s a general Tree-sitter issue, but the Tree-sitter grammar is written slightly differently from a typical BNF that I am used to.

A traditional (E)BNF, like Scala 3 Syntax is written as unambiguous deeply hierarchal tokens as:

Expr ::= FunParams ('=>' | '?=>') Expr

| HkTypeParamClause '=>' Expr

| Expr1

Expr1 ::= ['inline'] 'if' '(' Expr ')' {nl} Expr [[semi] 'else' Expr]

....

| PostfixExpr [Ascription]

PostfixExpr ::= InfixExpr [id]

InfixExpr ::= PrefixExpr

| InfixExpr id [nl] InfixExpr

PrefixExpr ::= [PrefixOperator] SimpleExpr

SimpleExpr ::= SimpleRef

| Literal

| '_'

| BlockExpr

....

| SimpleExpr ArgumentExprs

In comparison, tree-sitter-scala is much flatter.

expression: $ => choice(

$.if_expression,

$.match_expression,

$.try_expression,

$.call_expression,

$.assignment_expression,

$.lambda_expression,

$.postfix_expression,

$.ascription_expression,

$.infix_expression,

$.prefix_expression,

....

$.generic_function,

),

This means that Tree-sitter often would run into a conflict where one snippet of code can be parsed as different meanings. Conflicting tokens section of the documentation addresses this. One of the ideas is lexical precedence, which is similar to operator precedence but different.

if 1 < 2 then 3

else 4 + 5

It’s odd to think this way, but the above code can be parsed in two different ways, which could result to 3 or 8. The normal way and:

(if 1 < 2 then 3

else 4) + 5

We might intuitively think that infix expression has somewhat low precedence, but it turns out that if expression must have even lower precedence.

Tree-sitter addresses this by assigning PREC ordering at the token level:

const PREC = {

control: 1,

...

infix: 6,

...

}

if_expression: $ => prec.right(PREC.control, seq(

'if',

...

)),

infix_expression: $ => prec.left(PREC.infix, seq(

field('left', $.expression),

...

)),

Here, the higher number has higher precedence.

Ideally we should introduce more levels so control structure won’t be mixed into

lower expressions like call_expression and infix_expression.

Thus far, my attempt to add more expression layer has increased the build time so much that I can’t tell it would complete or not.

string tokens

One feature that I didn’t fully understand in the beginning, and to be honest I am not sure if I still do is automatic keyword extraction.

Supposedly this feature prevents string with keyword prefix like yieldSomething to be interpreted as yield Something. What I am not sure is if this prevents yield to be interpreted as an identifier.

Take the following code for example:

def main() =

if

val a = false

a

then b

else c

Prior to making if condition indentable, Tree-sitter happily parsed the above code as follows:

$ tree-sitter parse examples/A.scala

(compilation_unit [0, 0] - [6, 0]

(function_definition [0, 0] - [6, 0]

name: (identifier [0, 4] - [0, 8])

parameters: (parameters [0, 8] - [0, 10])

body: (indented_block [1, 2] - [6, 0]

(if_expression [1, 2] - [5, 8]

condition: (assignment_expression [2, 4] - [3, 5]

left: (postfix_expression [2, 4] - [2, 9]

(identifier [2, 4] - [2, 7])

(identifier [2, 8] - [2, 9]))

right: (postfix_expression [2, 12] - [3, 5]

(boolean_literal [2, 12] - [2, 17])

(identifier [3, 4] - [3, 5])))

consequence: (identifier [4, 7] - [4, 8])

alternative: (identifier [5, 7] - [5, 8])))))

Note that this was parsed as assignment_expresion between two postfix_expressions. In other words, Tree-sitter parsed val as an identifier, which should never happen.

Somewhat related, if we want to not capture identifier in end_marker etc,

and just reused the regex, Tree-sitter would bucket it up and show a confusing error message:

Non-terminal symbol 'identifier' cannot be used as the word token

The proper workaround for this is to alias the identifier with a string literal:

alias($.identifier, '_end_ident'),

optional braces part 2, the pull request

On Wednesday, I sent ‘Optional braces, part 2’ (#62), and I’ve been adding a few commits addressing some of the issues that I described above.

An interesting thing about Neovim’s Tree-sitter support is that we can point at the directory or Github repository on where to grab the generated C code, and test if the code hightlighting actually improved.

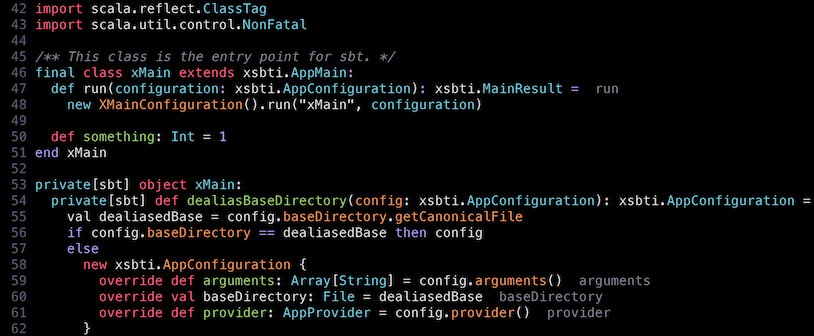

Before:

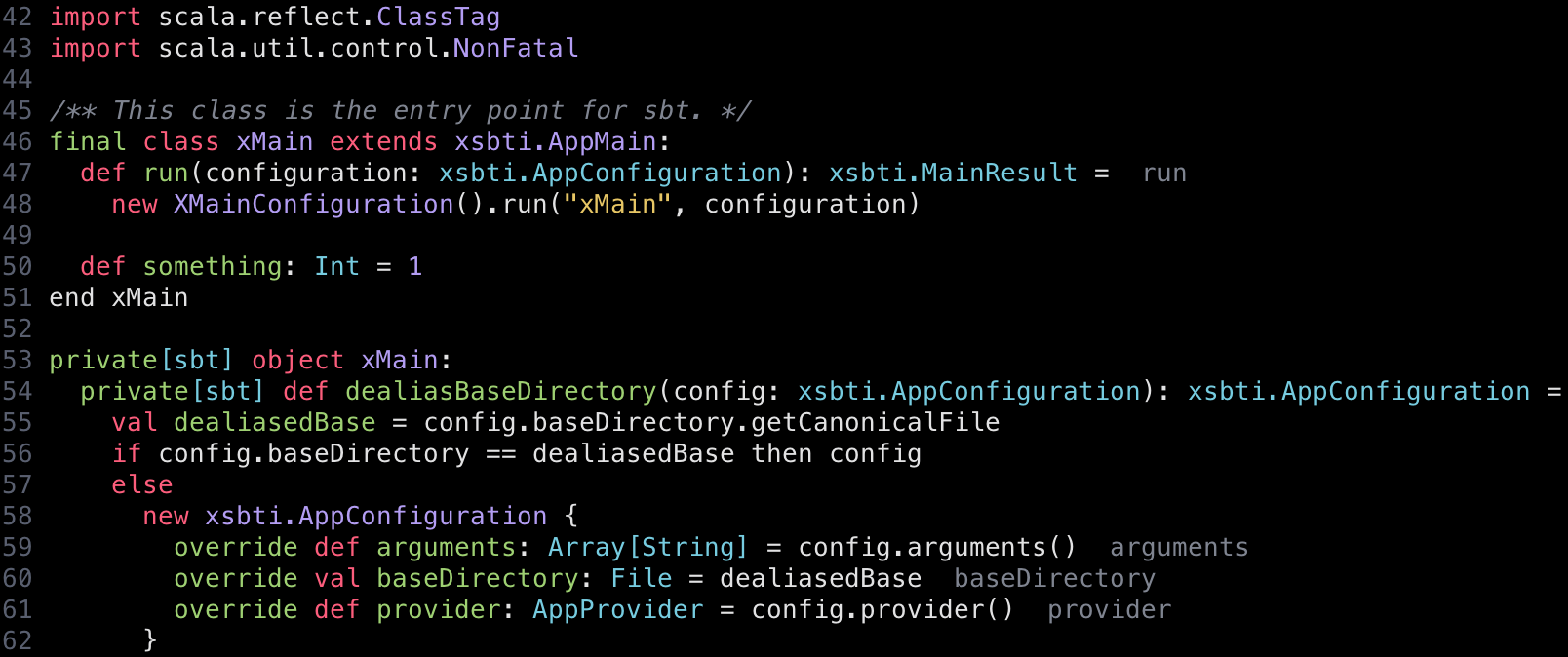

After:

This is by no means complete support of the new Scala 3 syntax, but I think it’s a decent improvement over the status quo.

Neovim setup to use a tree-sitter-scala fork

Given that some of the pull request has been open since February, I am not really sure if my PR would be considered anytime soon.

Thankfully nvim-treesitter comes with a built-in mechanism to override a grammar to another implementation. Here’s the setup to try this out on your machine.

rm -f ~/.local/share/nvim/site/pack/packer/start/nvim-treesitter/parser/scala.so

lua/plugins.lua

vim.cmd [[packadd packer.nvim]]

return require('packer').startup(function()

-- Packer can manage itself

use 'wbthomason/packer.nvim'

use 'tanvirtin/monokai.nvim'

use 'sainnhe/sonokai'

use 'nvim-treesitter/nvim-treesitter'

end)

init.vim

lua << END

require('plugins')

require'nvim-treesitter.configs'.setup {

-- A list of parser names, or "all". Don't include "scala" here.

ensure_installed = { "c", "lua", "rust" },

sync_install = false,

auto_install = true,

highlight = {

enable = true,

additional_vim_regex_highlighting = false,

},

}

local parser_config = require "nvim-treesitter.parsers".get_parser_configs()

parser_config.scala = {

install_info = {

-- url can be Git repo or a local directory:

-- url = "~/work/tree-sitter-scala",

url = "https://github.com/eed3si9n/tree-sitter-scala.git",

branch = "fork-integration",

files = {"src/parser.c", "src/scanner.c"},

requires_generate_from_grammar = false,

},

}

END

fast Scala 3 parsing

Let’s try parsing some Scala 3 compiler code. Here are some of the largest source file in Scala 3 compiler:

$ find $HOME/work/dotty -name '*.scala' -type f -exec wc -l {} + | sort -rn | head -n 10

250913 total

223621 total

7122 ~/work/dotty/tests/run/bridges.scala

5835 ~/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/core/Types.scala

4313 ~/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/backend/sjs/JSCodeGen.scala

4196 ~/work/dotty/library/src/scala/quoted/Quotes.scala

3971 ~/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/parsing/Parsers.scala

3748 ~/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/typer/Typer.scala

3002 ~/work/dotty/tests/disabled/reflect/run/t7556/mega-class_1.scala

2886 ~/work/dotty/compiler/src/scala/quoted/runtime/impl/QuotesImpl.scala

$ scalac --version

Scala compiler version 3.2.1 -- Copyright 2002-2022, LAMP/EPFL

$ time scalac $HOME/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/core/Types.scala -Ystop-after:parser -Ylog:parser -d /tmp/target/

scalac $HOME/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/core/Types.scala -d 4.02s user 0.31s system 219% cpu 1.980 total

$ time tree-sitter parse $HOME/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/core/Types.scala -q

/Users/xxx/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/core/Types.scala 60 ms (ERROR [111, 22] - [111, 27])

tree-sitter parse -q 0.07s user 0.00s system 96% cpu 0.073 total

$ time scalac $HOME/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/parsing/Parsers.scala -Ystop-after:parser -Ylog:parser -d /tmp/target/

scalac $HOME/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/parsing/Parsers.scala 3.54s user 0.29s system 206% cpu 1.854 total

$ time tree-sitter parse $HOME/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/parsing/Parsers.scala -q

/Users/xxx/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/parsing/Parsers.scala 26 ms (ERROR [49, 4] - [49, 8])

tree-sitter parse -q 0.03s user 0.00s system 91% cpu 0.040 total

For shorter code like compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/typer/ErrorReporting.scala, the tree-sitter self-reports single digit milli second:

$ time scalac $HOME/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/typer/ErrorReporting.scala -Ystop-after:parser -Ylog:parser -d /tmp/target/

scalac -Ystop-after:parser -Ylog:parser -d /tmp/target/ 2.88s user 0.27s system 182% cpu 1.736 total

$ time tree-sitter parse $HOME/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/typer/ErrorReporting.scala -q

/Users/xxx/work/dotty/compiler/src/dotty/tools/dotc/typer/ErrorReporting.scala 5 ms (ERROR [22, 61] - [22, 66])

tree-sitter parse -q 0.01s user 0.00s system 85% cpu 0.013 total

| source | lines | Dotty | tree-sitter | speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Types.scala |

5835 |

1980ms |

73ms |

27x |

Parsers.scala |

3971 |

1854ms |

40ms |

46x |

ErrorReporting.scala |

361 |

1736ms |

13ms |

134x |

Even setting aside the absolute speed of tree-sitter, note that increase in 5474 lines results in only additional 60ms, as opposed to 244ms in Dotty. This indicates that Dotty parses around 20 sloc/ms whereas tree-sitter parses 91 sloc/ms. Granted these parsing still contains partial errors because the grammar doesn’t fully support Scala 3 syntax yet, my guess is that it won’t increase the parsing speed.

summary

- Tree-sitter is a language-agnostic parser generator, targeting C language, which is capable of fast, incremental, and robust parsing that permits partial errors in the source code.

- Initially adopted by Atom, Neovim is planning to adopt this to provide richer language features, like syntax highlight and folding.

- Current challenge for Scala is lack of Scala 3 syntax support in tree-sitter/tree-sitter-scala, which ‘Optional braces, part 2’ (#62) and other PRs attempt to improve.

- Neovim can be setup to use eed3si9n/tree-sitter-scala#fork-integration branch.

see also

Tree-sitter’s lack of Scala 3 syntax support has been a topic that’s been brought up by few others as well:

- On Scala Users forum Graham Brown asked about Scala 3 Syntax Highlighting in vim in May 2021.

- Github issue ‘Scala 3 syntax support?’ #43, opened in Nov 2021 has 41 likes, and no comments from the maintainers as of this writing.

- Chris Kipp brought up ‘Scala 3 syntax support in “other” editors’ on Scala Contributors forum in Nov 2021.