monads are fractals

On my way back from Uppsala, my mind wandered to a conversation I had with a collegue about the intuition of monads, which I pretty much butchered at the time. As I was mulling this over, it dawned on me.

monads are fractals

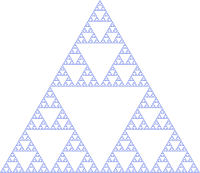

The above is a fractal called Sierpinski triangle, the only fractal I can remember to draw. Fractals are self-similar structure like the above triangle, in which the parts are similar to the whole (in this case exactly half the scale as parent triangle).

Monads are fractals. Given a monadic data structure, its values can be composed to form another value of the data structure. This is why it’s useful to programming, and this is why it occurrs in many situations.

Let’s look at some examples:

scala> List(List(1), List(2, 3), List(4))

res0: List[List[Int]] = List(List(1), List(2, 3), List(4))

The above is a List of List of Int. We can intuitively crunch this into a List of Int like this:

scala> List(1, 2, 3, 4)

res1: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

For 1 to form List(1) we can also provide a single-parameter constructor unit: A => F[A]. This allows us to crunch 1 and 4 along with List(2, 3):

scala> List(List.apply(1), List(2, 3), List.apply(4))

res2: List[List[Int]] = List(List(1), List(2, 3), List(4))

The type signature of crunching, also known as join is F[F[A]] => F[A].

monoids

The crunching operation reminded me of monoids, which consists of:

trait Monoid[A] {

def mzero: A

def mappend(a1: A, a2: A): A

}

We can use monoid to abstract out operations on two items:

scala> List(1, 2, 3, 4).foldLeft(0) { _ + _ }

res4: Int = 10

scala> List(1, 2, 3, 4).foldLeft(1) { _ * _ }

res5: Int = 24

scala> List(true, false, true, true).foldLeft(true) { _ && _ }

res6: Boolean = false

scala> List(true, false, true, true).foldLeft(false) { _ || _ }

res7: Boolean = true

One aspect of monoid I want to highlight here is that data type alone is not enough to define the monoid. The pair (Int, +) forms a monoid. Or Ints are monoid under addition. See https://twitter.com/jessitron/status/438432946383360000 for more on this.

List is a monad under ++

When List of List of Int crunches into a List of Int, it’s obvious that it uses something like foldLeft and ++ to make List[Int].

scala> List(List.apply(1), List(2, 3), List.apply(4)).foldLeft(List(): List[Int]) { _ ++ _ }

res8: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

But it could have been something else. For example, it could return a list of sums.

scala> List(List.apply(1), List(2, 3), List.apply(4)).foldLeft(List(): List[Int]) { (acc, xs) => acc :+ xs.sum }

res9: List[Int] = List(1, 5, 4)

That’s a contrived example, but it’s important to think of the composition semantics that a monad encapsulates.

Option is a monad under…?

Let’s look at Option too. Remember the type signature of monadic crunching is F[F[A]] => F[A], so what we need as examples are nested Options, not a list of Options.

scala> Some(None: Option[Int]): Option[Option[Int]]

res10: Option[Option[Int]] = Some(None)

scala> Some(Some(1): Option[Int]): Option[Option[Int]]

res11: Option[Option[Int]] = Some(Some(1))

scala> None: Option[Option[Int]]

res12: Option[Option[Int]] = None

Here’s what I came up with to crunch Option of Option of Int into an Option of Int.

scala> (Some(None: Option[Int]): Option[Option[Int]]).foldLeft(None: Option[Int]) { (_, _)._2 }

res20: Option[Int] = None

scala> (Some(Some(1): Option[Int]): Option[Option[Int]]).foldLeft(None: Option[Int]) { (_, _)._2 }

res21: Option[Int] = Some(1)

scala> (None: Option[Option[Int]]).foldLeft(None: Option[Int]) { (_, _)._2 }

res22: Option[Int] = None

So Option apparenlty is a monad under _2. In this case I don’t know if it’s immediately obvious from the implemetation, but the idea is to propagate None, which represents a failure.

what about the laws?

So far we have two functions join and unit. We actually need one more, which is map.

join: F[F[A]] => F[A]unit: A => F[A]map: F[A] => (A => B) => F[B]

Given List[List[List[Int]]], we can write the accociative law by crunching the outer most list first or middle list first. The following is from one of the chapter notes of Functional Programming in Scala:

scala> val xs: List[List[List[Int]]] = List(List(List(1,2), List(3,4)), List(List(5,6), List(7,8)))

xs: List[List[List[Int]]] = List(List(List(1, 2), List(3, 4)), List(List(5, 6), List(7, 8)))

scala> val ys1 = xs.flatten

ys1: List[List[Int]] = List(List(1, 2), List(3, 4), List(5, 6), List(7, 8))

scala> val ys2 = xs map {_.flatten}

ys2: List[List[Int]] = List(List(1, 2, 3, 4), List(5, 6, 7, 8))

scala> ys1.flatten

res30: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8)

scala> ys2.flatten

res31: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8)

This can be generalized as:

join(join(m)) assert_=== join(map(m)(join))

Here are the identity laws also from the same notes:

join(unit(m)) assert_=== m

join(map(m)(unit)) assert_=== m

This illustrates that we can define a monad without using flatMap. In actual coding, however, we tend to deal with monads by chaining flatMaps using for comprehension, which combines map and join.

State monad

When writing in purely functional style, one pattern that arises often is passing a value that represents some state.

val (d0, _) = Tetrix.init()

val (d1, _) = Tetrix.nextBlock(d0)

val (d2, moved0) = Tetrix.moveBlock(d1, LEFT)

val (d3, moved1) =

if (moved0) Tetrix.moveBlock(d2, LEFT)

else (d2, moved0)

The passing of the state object becomes boilerplate, and error-prone especially when you start to compose the state transition using function calls. State monad is a monad that encapsulates state transition S => (S, A).

After rewriting Tetrix.nextBlock and Tetrix.moveBlock functions to return State[GameSate, A], we can write the above code as:

def nextLL: State[GameState, Boolean] = for {

_ <- Tetrix.nextBlock

moved0 <- Tetrix.moveBlock(LEFT)

moved1 <- if (moved0) Tetrix.moveBlock(LEFT)

else State.state(moved0)

} yield moved1

nextLL.eval(Tetrix.init())

It’s hard to say whether it’s good thing to be able to write for comprehension since it possibly makes less sense to those who are not informed about the State monad. One good thing is that we now have a type that automates passing d0, d1, d2, …

What I want to highlight here is that State monad is a fractal just like List. moveBlock function returns a State and for comprehension is State of State. In the above example, two calls to moveBlock function can be factored out:

def leftLeft: State[GameState, Boolean] = for {

moved0 <- Tetrix.moveBlock(LEFT)

moved1 <- if (moved0) Tetrix.moveBlock(LEFT)

else State.state(moved0)

} yield moved1

def nextLL: State[GameState, Boolean] = for {

_ <- Tetrix.nextBlock

moved <- leftLeft

} yield moved

nextLL.eval(Tetrix.init())

This allows us to create mini imperative style programs that can be combined functionally. Note the semantics of for is limited to one monad at a time.

StateT monad transformer

In the above, my hypothetical moveBlock returns State[GameState, Boolean]. When it returns false the block has either hit a wall or another block so no further action will be taken. If true do something, is like a mantra of imperative programming. It’s also a code smell for functional programming, because you likely want Option[A] instead. To use State and Option simultaneously, we can use StateT. Now all state transition will also be wrapped in Option.

Suppose nextBlock will place the current block at x position 1, and moving left beyond 0 will fail.

scala> import scalaz._, Scalaz._

import scalaz._

import Scalaz._

scala> :paste

// Entering paste mode (ctrl-D to finish)

type StateTOption[S, A] = StateT[Option, S, A]

object StateTOption extends StateTInstances with StateTFunctions {

def apply[S, A](f: S => Option[(S, A)]) = StateT[Option, S, A] { s =>

f(s)

}

}

case class GameState(blockPos: Int)

sealed trait Direction

case object LEFT extends Direction

case object RIGHT extends Direction

case object DOWN extends Direction

object Tetrix {

def nextBlock = StateTOption[GameState, Unit] { s =>

Some(s.copy(blockPos = 1), ())

}

def moveBlock(dir: Direction) = StateTOption[GameState, Unit] { s =>

dir match {

case LEFT =>

if (s.blockPos == 0) None

else Some((s.copy(blockPos = s.blockPos - 1), ()))

case RIGHT => Some((s.copy(blockPos = s.blockPos + 1), ()))

case DOWN => Some((s, ()))

}

}

}

// Exiting paste mode, now interpreting.

scala> def leftLeft: StateTOption[GameState, Unit] = for {

_ <- Tetrix.moveBlock(LEFT)

_ <- Tetrix.moveBlock(LEFT)

} yield ()

leftLeft: StateTOption[GameState,Unit]

scala> def nextLL: StateTOption[GameState, Unit] = for {

_ <- Tetrix.nextBlock

_ <- leftLeft

} yield ()

nextLL: StateTOption[GameState,Unit]

scala> nextLL.eval(GameState(0))

res0: Option[Unit] = None

scala> def nextRLL: StateTOption[GameState, Unit] = for {

_ <- Tetrix.nextBlock

_ <- Tetrix.moveBlock(RIGHT)

_ <- leftLeft

} yield ()

nextRLL: StateTOption[GameState,Unit]

scala> nextRLL.eval(GameState(0))

res1: Option[Unit] = Some(())

The above shows that moving left-left failed, but calling right-left-left succeeded. In this simple example monad stacked nicely, but this could get hairly.

scopt as a monad

Another thing I was thinking on the plane was scopt, which is a command line parsing library. One of the issue that’s been raised about scopt is that the parser it generates is not composable.

If you think about it, scopt is essentially a State. You pass in a config case class in one end, and after series of transformations you get the config back. Here’s a hypothetical code of how scopt could look like:

val parser = {

val builder = scopt.OptionParser.builder[Config]("scopt")

import builder._

for {

_ <- head("scopt", "3.x")

_ <- opt[Int]('f', "foo") action { (x, c) => c.copy(foo = x) }

_ <- arg[File]("<source>") action { (x, c) => c.copy(source = x) }

_ <- arg[File]("<targets>...") unbounded() action { (x, c) => c.copy(targets = c.targets :+ x) }

} yield ()

}

parser.parse("--foo a.txt b.txt c.txt", Config()) match {

case Some(c) =>

caes None =>

}

If the parser’s type is OptionParser[Unit], then opt[Int] will also be a OptionParser[A]. This allows us to factor out some of the options into a sub-parser and reuse it given Config can be reused.

Free monad

Perhaps no other monads feels more fractal-like than Free monads. List and Option are fractal too, but with Free you’re involved in the construction of a nanotech monomer, which then repeats itself to become a giant structure on its own.

For example, using Tuple2[A, Next], Free can form a monad that acts like a list by embedding another Tuple2[A, Next] into Next like Tuple2[A, Tuple2[A, Next]], and so on.

What we end up is a data structure that’s free of additional context other than the fact that it’s a fractal. You’re responsible for destructuring the result and do something meaningful. This approach could be simpler than monad transformer.

scala> import scalaz._, Scalaz._

import scalaz._

import Scalaz._

scala> :paste

// Entering paste mode (ctrl-D to finish)

case class GameState(blockPos: Int)

sealed trait Direction

case object LEFT extends Direction

case object RIGHT extends Direction

case object DOWN extends Direction

sealed trait Tetrix[Next]

object Tetrix {

case class NextBlock[Next](next: Next) extends Tetrix[Next]

case class MoveBlock[Next](dir: Direction, next: Next) extends Tetrix[Next]

implicit val gameCommandFunctor: Functor[Tetrix] = new Functor[Tetrix] {

def map[A, B](fa: Tetrix[A])(f: A => B): Tetrix[B] = fa match {

case n: NextBlock[A] => NextBlock(f(n.next))

case m: MoveBlock[A] => MoveBlock(m.dir, f(m.next))

}

}

def nextBlock: Free[Tetrix, Unit] = Free.liftF[Tetrix, Unit](NextBlock(()))

def moveBlock(dir: Direction): Free[Tetrix, Unit] =

Free.liftF[Tetrix, Unit](MoveBlock(dir, ()))

def eval(s: GameState, cs: Free[Tetrix, Unit]): Option[Unit] =

cs.resume.fold({

case NextBlock(next) =>

eval(s.copy(blockPos = 1), next)

case MoveBlock(dir, next) =>

dir match {

case LEFT =>

if (s.blockPos == 0) None

else eval(s.copy(blockPos = s.blockPos - 1), next)

case RIGHT => eval(s.copy(blockPos = s.blockPos + 1), next)

case DOWN => eval(s, next)

}

},

{ r: Unit => Some(()) })

}

// Exiting paste mode, now interpreting.

scala> def leftLeft: Free[Tetrix, Unit] = for {

_ <- Tetrix.moveBlock(LEFT)

_ <- Tetrix.moveBlock(LEFT)

} yield ()

leftLeft: scalaz.Free[Tetrix,Unit]

scala> def nextLL: Free[Tetrix, Unit] = for {

_ <- Tetrix.nextBlock

_ <- leftLeft

} yield ()

nextLL: scalaz.Free[Tetrix,Unit]

scala> Tetrix.eval(GameState(0), nextLL)

res0: Option[Unit] = None

scala> def nextRLL: Free[Tetrix, Unit] = for {

_ <- Tetrix.nextBlock

_ <- Tetrix.moveBlock(RIGHT)

_ <- leftLeft

} yield ()

nextRLL: scalaz.Free[Tetrix,Unit]

scala> Tetrix.eval(GameState(0), nextRLL)

res1: Option[Unit] = Some(())

Except for the type signature, the program portion of the code is identical to the one using StateTOption.

There’s a bit of tradeoff on using this since we’ll be responsible for implementing the context, but there’s less mess on the type after the initial setup.

summary

Monads are self-repeating structure like fractals, which could be expressed as a function join: F[F[A]] => F[A]. This property enables monadic values to be composed into larger monadic values. Just like monoid’s mappend, join can encapsulate some additional of semantics (for example Option and State). Whenever you find self-repeating structure, you might be looking at a monad.

The composition of monadic types could be achieved via monad tranformers, but it is notorious for getting complicated. Free may offer an alternative of providing monadic DSL.