console games in Scala

I’ve been thinking about rich console applications, the kind of apps that can display things graphically, not just appending lines at the end. Here are some info, enough parts to be able to write Tetris.

ANSI X3.64 control sequences

To display some text at an arbitrary location on a termial screen, we first need to understand what a terminal actually is. In the middle of 1960s, companies started selling minicomputers such as PDP-8, and later PDP-11 and VAX-11. These were of a size of a refrigerator, purchased by “computer labs”, and ran operating systems like RT-11 and the original UNIX system that supported up many simultaneous users (12 ~ hundreds?). The users connected to a minicomputer using a physical terminal that looks like a monochrome screen and a keyboard. The classic terminal is VT100 that was introduced in 1978 by DEC.

VT100 supports 80x24 characters, and it was one of the first terminals to adopt ANSI X3.64 standard for cursor control. In other words, programs can output a character sequence to move the cursor around and display text at an aribitrary location. Modern terminal apps are sometimes called terminal emulators because they emulate the behavior of terminals such as VT100.

Good reference for the VT100 control sequences can be found at:

CUP (Cursor Position)

ESC [ <y> ; <x> HCUP Cursor Position*Cursor moves to

<x>; <y>coordinate within the viewport, where<x>is the column of the<y>line

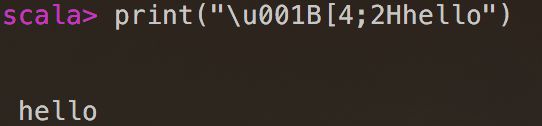

In the above, ESC stands for 0x1B. Here’s a Scala code to display “hello” at (2, 4):

print("\u001B[4;2Hhello")

CUB (Cursor Backward)

ESC [ <n> DCUB Cursor BackwardCursor backward (Left) by

<n>

This is a useful control sequence to implement a progress bar.

(1 to 100) foreach { i =>

val dots = "." * ((i - 1) / 10)

print(s"\u001B[100D$i% $dots")

Thread.sleep(10)

}

Saving cursor position

ESC [ s**With no parameters, performs a save cursor operation like DECSC

ESC [ u**With no parameters, performs a restore cursor operation like DECRC

These can be used to save and restore the current cursor position.

Text formatting

ESC [ <n> mSGR Set Graphics RenditionSet the format of the screen and text as specified by

<n>

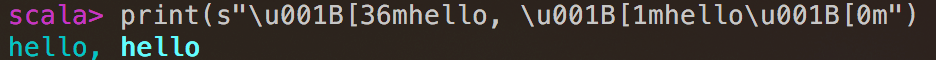

Using this sequence, we can change the color of the text. For example, 36 is Foreground Cyan, 1 is Bold, and 0 is reset to default.

print("\u001B[36mhello, \u001B[1mhello\u001B[0m")

ED (Erase in Display)

ESC [ <n> JED Erase in DisplayReplace all text in the current viewport/screen specified by

<n>with space characters

Specifying 2 for <n> means erasing the entire viewport:

print("\u001B[2J")

EL (Erase in Line)

ESC [ <n> KEL Erase in LineReplace all text on the line with the cursor specified by

<n>with space characters

Especially when the text is scrolling up and down, it’s convenient to be able to erase the entire line. Specifying 2 for <n> does that:

println("\u001B[2K")

SU (Scroll Up)

ESC [ <n> SSU Scroll UpScroll text up by

<n>. Also known as pan down, new lines fill in from the bottom of the screen

Let’s say you want to take over the bottom half of the screen, but let the top half be used for scrolling text. Scroll Up sequence can be used to shift the text position upwards.

On REPL, we can do something like:

- Save the cursor position

- Move the cursor to

(1, 4) - Scroll up by 1

- Erase the line

- Print something

- Restore the cursor position

scala> print("\u001B[s\u001B[4;1H\u001B[S\u001B[2Ksomething 1\u001B[u")

scala> print("\u001B[s\u001B[4;1H\u001B[S\u001B[2Ksomething 2\u001B[u")

scala> print("\u001B[s\u001B[4;1H\u001B[S\u001B[2Ksomething 3\u001B[u")

Jansi

On JVM, there’s a library called Jansi that provides support for ANSI X3.64 control sequences. When some of the sequences are not available on Windows, it uses system API calls to emulate it.

Here’s how we can write the cursor position example using Jansi.

scala> import org.fusesource.jansi.{ AnsiConsole, Ansi }

import org.fusesource.jansi.{AnsiConsole, Ansi}

scala> AnsiConsole.out.print(Ansi.ansi().cursor(6, 10).a("hello"))

hello

Box drawing characters

Another innovation of VT100 was adding custom characters for box drawing. Today, they are part of Unicode box-drawing symbols.

┌───┐

│ │

└───┘

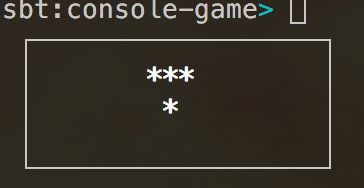

Here’s a small app that draws a box and a Tetris block.

package example

import org.fusesource.jansi.{ AnsiConsole, Ansi }

object ConsoleGame extends App {

val b0 = Ansi.ansi().saveCursorPosition().eraseScreen()

val b1 = drawbox(b0, 2, 6, 20, 5)

val b2 = b1

.bold

.cursor(7, 10)

.a("***")

.cursor(8, 10)

.a(" * ")

.reset()

.restoreCursorPosition()

AnsiConsole.out.println(b2)

def drawbox(b: Ansi, x0: Int, y0: Int, w: Int, h: Int): Ansi = {

require(w > 1 && h > 1)

val topStr = "┌".concat("─" * (w - 2)).concat("┐")

val wallStr = "│".concat(" " * (w - 2)).concat("│")

val bottomStr = "└".concat("─" * (w - 2)).concat("┘")

val top = b.cursor(y0, x0).a(topStr)

val walls = (0 to h - 2).toList.foldLeft(top) { (b: Ansi, i: Int) =>

b.cursor(y0 + i + 1, x0).a(wallStr)

}

walls.cursor(y0 + h - 1, x0).a(bottomStr)

}

}

BuilderHelper datatype

A minor annoyance with Jansi is that if you want to compose the drawings, we need to keep passing the Ansi object arround in the correct order. This can be solved quickly using State datatype. Since the name State might get confusing with game’s state, I am going to call it BuilderHelper.

package example

class BuilderHelper[S, A](val run: S => (S, A)) {

def map[B](f: A => B): BuilderHelper[S, B] = {

BuilderHelper[S, B] { s0: S =>

val (s1, a) = run(s0)

(s1, f(a))

}

}

def flatMap[B](f: A => BuilderHelper[S, B]): BuilderHelper[S, B] = {

BuilderHelper[S, B] { s0: S =>

val (s1, a) = run(s0)

f(a).run(s1)

}

}

}

object BuilderHelper {

def apply[S, A](run: S => (S, A)): BuilderHelper[S, A] = new BuilderHelper(run)

def unit[S](run: S => S): BuilderHelper[S, Unit] = BuilderHelper(s0 => (run(s0), ()))

}

This lets us refactor the drawing code as follows:

package example

import org.fusesource.jansi.{ AnsiConsole, Ansi }

object ConsoleGame extends App {

val drawing: BuilderHelper[Ansi, Unit] =

for {

_ <- Draw.saveCursorPosition

_ <- Draw.eraseScreen

_ <- Draw.drawBox(2, 4, 20, 5)

_ <- Draw.drawBlock(10, 5)

_ <- Draw.restoreCursorPosition

} yield ()

val result = drawing.run(Ansi.ansi())._1

AnsiConsole.out.println(result)

}

object Draw {

def eraseScreen: BuilderHelper[Ansi, Unit] =

BuilderHelper.unit { _.eraseScreen() }

def saveCursorPosition: BuilderHelper[Ansi, Unit] =

BuilderHelper.unit { _.saveCursorPosition() }

def restoreCursorPosition: BuilderHelper[Ansi, Unit] =

BuilderHelper.unit { _.restoreCursorPosition() }

def drawBlock(x: Int, y: Int): BuilderHelper[Ansi, Unit] = BuilderHelper.unit { b: Ansi =>

b.bold

.cursor(y, x)

.a("***")

.cursor(y + 1, x)

.a(" * ")

.reset

}

def drawBox(x0: Int, y0: Int, w: Int, h: Int): BuilderHelper[Ansi, Unit] = BuilderHelper.unit { b: Ansi =>

require(w > 1 && h > 1)

val topStr = "┌".concat("─" * (w - 2)).concat("┐")

val wallStr = "│".concat(" " * (w - 2)).concat("│")

val bottomStr = "└".concat("─" * (w - 2)).concat("┘")

val top = b.cursor(y0, x0).a(topStr)

val walls = (0 to h - 2).toList.foldLeft(top) { (bb: Ansi, i: Int) =>

bb.cursor(y0 + i + 1, x0).a(wallStr)

}

walls.cursor(y0 + h - 1, x0).a(bottomStr)

}

}

All I am doing is here is avoiding creation of b0, b1, b2 etc, so if this code is confusing you don’t have to use BuilderHelper.

Input sequence

Thus far we’ve looked at control sequences sent by the program, but the same protocol can be used by the terminal to talk to the program via the keyboard. Under ANSI X3.64 compatible mode, the arrow keys on VT100 sent CUU (Cursor Up), CUD (Cursor Down), CUF (Cursor Forward), and CUB (Cursor Back) respectively. This behavior remains the same for terminal emulators such as iTerm2.

In other words, when you hit Left arrow key ESC + "[D", or "\u001B[D", is sent to the standard input. We can read bytes off of the standard input one by one and try to parse the control sequence.

var isGameOn = true

var pending = ""

val escStr = "\u001B"

val escBracket = escStr.concat("[")

def clearPending(): Unit = { pending = "" }

while (isGameOn) {

if (System.in.available > 0) {

val x = System.in.read.toByte

if (pending == escBracket) {

x match {

case 'A' => println("Up")

case 'B' => println("Down")

case 'C' => println("Right")

case 'D' => println("Left")

case _ => ()

}

clearPending()

} else if (pending == escStr) {

if (x == '[') pending = escBracket

else clearPending()

} else

x match {

case '\u001B' => pending = escStr

case 'q' => isGameOn = false

// Ctrl+D to quit

case '\u0004' => isGameOn = false

case c => println(c)

}

} // if

}

This is not that bad for simple games, but it could get more tricky if the combination gets more advanced, or we if start to take Windows terminals into consideration.

JLine2, maybe

On JVM, there’s JLine2 that implements a concept called KeyMap. KeyMap maps a sequence of bytes into an Operation.

Because JLine is meant to be a line editor, like what you see on Bash or sbt shell with history and tab completion, the operations reflect that. For example, the up arrow is bound to Operation.PREVIOUS_HISTORY. Using JLine2, the code above can be written as follows:

import jline.console.{ ConsoleReader, KeyMap, Operation }

var isGameOn = true

val reader = new ConsoleReader()

val km = KeyMap.keyMaps().get("vi-insert")

while (isGameOn) {

val c = reader.readBinding(km)

val k: Either[Operation, String] =

if (c == Operation.SELF_INSERT) Right(reader.getLastBinding)

else Left(c match { case op: Operation => op })

k match {

case Right("q") => isGameOn = false

case Left(Operation.VI_EOF_MAYBE) => isGameOn = false

case _ => println(k)

}

}

I kind of like the raw simplicity of reading from System.in, but the JLine2 looks a bit more cleaned up, so it’s up whatever you are more confortable with.

Listening to keyboard in the background

What System.in code makes it clear is that waiting for keyboard input is equivalent of reading from a file. Another observation is that the most of the microseconds will be spent waiting for the user. So what we want to do, is grab user inputs in the background, and when we are ready periodically pick them up, and handle them.

We can do this by writing the keypress events into Apache Kafka. Haha, I am just kidding. Except, not completely. Kafka is a log system that programs can write events into, and other programs can read off of it when they want to.

Here’s what I did:

import jline.console.{ ConsoleReader, KeyMap, Operation }

import scala.concurrent.{ blocking, Future, ExecutionContext }

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicBoolean

import java.util.concurrent.ArrayBlockingQueue

val reader = new ConsoleReader()

val isGameOn = new AtomicBoolean(true)

val keyPressses = new ArrayBlockingQueue[Either[Operation, String]](128)

import ExecutionContext.Implicits._

// inside a background thread

val inputHandling = Future {

val km = KeyMap.keyMaps().get("vi-insert")

while (isGameOn.get) {

blocking {

val c = reader.readBinding(km)

val k: Either[Operation, String] =

if (c == Operation.SELF_INSERT) Right(reader.getLastBinding)

else Left(c match { case op: Operation => op })

keyPressses.add(k)

}

}

}

// inside main thread

while (isGameOn.get) {

while (!keyPressses.isEmpty) {

Option(keyPressses.poll) foreach { k =>

k match {

case Right("q") => isGameOn.set(false)

case Left(Operation.VI_EOF_MAYBE) => isGameOn.set(false)

case _ => println(k)

}

}

}

// draw game etc..

Thread.sleep(100)

}

To spawn a new thread, I am using scala.concurrent.Future with the default global execution context. It blocks for user input, and then appends the key press into a ArrayBlockingQueue.

If you run this, and type Left, Right, 'q', you’d see something like:

Left(BACKWARD_CHAR)

Left(FORWARD_CHAR)

[success] Total time: 3 s

Processing the key presses

We can now move the current block using the key press. To track the position, let’s declare GameState datatype as follows:

case class GameState(pos: (Int, Int))

var gameState: GameState = GameState(pos = (6, 4))

Next we can define a state transition function based on the key press:

def handleKeypress(k: Either[Operation, String], g: GameState): GameState =

k match {

case Right("q") | Left(Operation.VI_EOF_MAYBE) =>

isGameOn.set(false)

g

// Left arrow

case Left(Operation.BACKWARD_CHAR) =>

val pos0 = gameState.pos

g.copy(pos = (pos0._1 - 1, pos0._2))

// Right arrow

case Left(Operation.FORWARD_CHAR) =>

val pos0 = g.pos

g.copy(pos = (pos0._1 + 1, pos0._2))

// Down arrow

case Left(Operation.NEXT_HISTORY) =>

val pos0 = g.pos

g.copy(pos = (pos0._1, pos0._2 + 1))

// Up arrow

case Left(Operation.PREVIOUS_HISTORY) =>

g

case _ =>

// println(k)

g

}

Finally we can call handleKeyPress inside the main while loop:

// inside the main thread

while (isGameOn.get) {

while (!keyPressses.isEmpty) {

Option(keyPressses.poll) foreach { k =>

gameState = handleKeypress(k, gameState)

}

}

drawGame(gameState)

Thread.sleep(100)

}

def drawGame(g: GameState): Unit = {

val drawing: BuilderHelper[Ansi, Unit] =

for {

_ <- Draw.drawBox(2, 2, 20, 10)

_ <- Draw.drawBlock(g.pos._1, g.pos._2)

_ <- Draw.drawText(2, 12, "press 'q' to quit")

} yield ()

val result = drawing.run(Ansi.ansi())._1

AnsiConsole.out.println(result)

}

Running this looks like this:

Combining with logs

Let’s see if we can combine this with the Scroll Up technique.

var tick: Int = 0

// inside the main thread

while (isGameOn.get) {

while (!keyPressses.isEmpty) {

Option(keyPressses.poll) foreach { k =>

gameState = handleKeypress(k, gameState)

}

}

tick += 1

if (tick % 10 == 0) {

info("something ".concat(tick.toString))

}

drawGame(gameState)

Thread.sleep(100)

}

def info(msg: String): Unit = {

AnsiConsole.out.println(Ansi.ansi()

.cursor(5, 1)

.scrollUp(1)

.eraseLine()

.a(msg))

}

Here, I am outputing a log every second at (1, 5) after scrolling the text upwards. This should retain all the logs in scroll buffer since I am not overwriting them.

I am sure that are lots of other techniques like that using ANSI control sequences. I’ve used Java libraries like Jansi and JLine2, but there’s nothing JVM or library dependent things in what I’ve shown.

A note on Windows 10

According to Windows Command-Line: The Evolution of the Windows Command-Line written in June, 2018:

In particular, the Console was lacking many features expected of modern *NIX compatible systems, such as the ability to parse & render ANSI/VT sequences used extensively in the *NIX world for rendering rich, colorful text and text-based UI’s. What, then, would be the point of building WSL if the user would not be able to see and use Linux tools correctly?

So, in 2014, a new, small, team was formed, charged with the task of unravelling, understanding, and improving the Console code-base … which by this time was ~28 years old - older than the developers working on it!

It seems like Console on Windows 10 are now compatible with VT100 control sequences, which also explains that we’ve been using Microsoft’s page as a reference guide.

Summary

The foundation of rich console application is based on physical terminal machines like VT100 from the 1970s, and ANSI X3.64 control sequences that standarized the byte sequence to control the cursor, text formats, etc. Modern terminal applications emulate the behaviors of these terminals.

Thus, if we can assume a good terminal app, all we need is an ability to println(...) the control sequences and listen for the standard input to write a rich console app. This should be possible in almost any programming language.

Libraries like JAnsi and JLine2 make some code nicer to read/write. In addition, they would provide fallback on Windows, but I am not sure how well it works on either modern Windows 10 vs older ones.

The code example used in this post is availble at https://github.com/eed3si9n/console-game.